Shadow banking system

The shadow banking system is a term for the collection of non-bank financial intermediaries that provide services similar to traditional commercial banksbut outside normal banking regulations.[1] The phrase "shadow banking" contains the pejorative connotation of back alley loan sharks. Many in the financial services industry find this phrase offensive and prefer the euphemism "market-based finance".[2]

This definition was first put forward by PIMCO (Pacific Investment Management Company) executive director Paul McCulley at a FED (Federal Reserve System) annual meeting in 2007.

Former US Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke provided the following definition in November 2013:

Shadow banking has grown in importance to rival traditional depository banking, and was a primary factor in the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007–2008 and the global recession that followed.[4][5][6]

Overview

Entities that make up the system

Importance

Many "shadow bank"-like institutions and vehicles have emerged in American and European markets, between the years 2000 and 2008, and have come to play an important role in providing credit across the global financial system.[26]

In a June 2008 speech, Timothy Geithner, then president and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, described the growing importance of what he called the "non-bank financial system": "In early 2007, asset-backed commercial paper conduits, in structured investment vehicles, in auction-rate preferred securities, tender option bonds and variable rate demand notes, had a combined asset size of roughly $2.2 trillion. Assets financed overnight in triparty repo grew to $2.5 trillion. Assets held in hedge funds grew to roughly $1.8 trillion. The combined balance sheets of the then five major investment banks totaled $4 trillion. In comparison, the total assets of the top five bank holding companies in the United States at that point were just over $6 trillion, and total assets of the entire banking system were about $10 trillion."[27]

In 2016, Benoît Cœuré (ECB executive board member) stated that controlling shadow banking should be the focus to avoid a future financial crisis, since the banks' leverage had been lowered.[28]

Risks or vulnerability

Shadow institutions are not subject to the same prudential regulations as depository banks, so that they do not have to keep as high financial reserves relative to their market exposure. Thus they can have a very high level of financial leverage, with a high ratio of debt relative to the liquid assets available to pay immediate claims. High leverage magnifies profits during boom periods and losses during downturns. This high leverage will also not be readily apparent to investors, and shadow institutions may therefore be able to create the appearance of superior performance during boom times by simply taking greater pro-cyclical risks. Money market funds have zero leverage and thus do not pose this risk feature of shadow banks.

Shadow institutions like SIVs and conduits, typically sponsored and guaranteed by commercial banks, borrowed from investors in short-term, liquid markets (such as the money market and commercial paper markets), so that they would have to repay and borrow again from these investors at frequent intervals. On the other hand, they used the funds to lend to corporations or to invest in longer-term, less liquid (i.e. harder to sell) assets. In many cases, the long-term assets purchased were mortgage-backed securities, sometimes called "toxic assets" or "legacy assets" in the press. These assets declined significantly in value as housing prices declined and foreclosures increased during 2007–2009.

In the case of investment banks, this reliance on short-term financing required them to return frequently to investors in the capital markets to refinance their operations. When the housing market began to deteriorate and their ability to obtain funds from investors through investments such as mortgage-backed securities declined, these investment banks could not refinance themselves. Investor refusal or inability to provide funds via the short-term markets was a primary cause of the failure of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers during 2008.

From a technical standpoint, these institutions are subject to market risk, credit risk and especially liquidity risk, since their liabilities are short term while their assets are more long term and illiquid. This creates a problem, as they are not depositary institutions and do not have direct or indirect access to the support of their central bank in its role as lender of last resort. Therefore, during periods of market illiquidity, they could go bankrupt if unable to refinance their short-term liabilities. They were also highly leveraged. This meant that disruptions in credit markets would make them subject to rapid deleveraging, meaning they would have to pay off their debts by selling their long-term assets.[29] A sell off of assets could cause further price declines of those assets and further losses and selloffs. In contrast to investment banks, money market funds do not go bankrupt—they distribute their assets (which are mainly short-term) pro rata to shareholders if their net asset value falls below $.9995 per share. Only two funds ever have failed to pay investors $1.00 per share. The Reserve Primary Fund paid $.99 per share to its shareholders and another fund paid its shareholders $.96 per share in 1994.

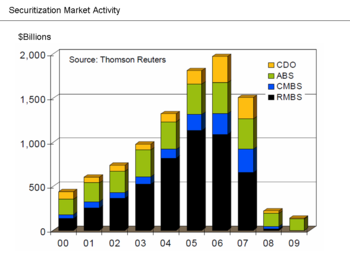

The securitization markets frequently tapped by the shadow banking system started to close down in the spring of 2007, with the first failure of auction-rate offerings to attract bids. As excesses associated with the U.S. housing bubble became widely understood and borrower default rates rose, residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) deflated. Tranched collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) lost value as default rates increased beyond the levels projected by their associated agency credit ratings. Commercial mortgage-backed securities suffered from association and from a general decline in economic activity, and the entire complex nearly shut down in the fall of 2008. More than a third of the private credit markets thus became unavailable as a source of funds.[30] In February 2009, Ben Bernanke stated that securitization markets remained effectively shut, with the exception of conforming mortgages, which could be sold to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.[31]

U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner has stated that the "combined effect of these factors was a financial system vulnerable to self-reinforcing asset price and credit cycles."[27]

In January 2012, the global Financial Stability Board announced its intention to further regulate the shadow banking system, in the interests of the real economy.[32]

History and origin of the term

The term "shadow banking system" is attributed to Paul McCulley of PIMCO, who coined it at Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City's Economic Symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in 2007 where he defined it as "the whole alphabet soup of levered up non-bank investment conduits, vehicles, and structures."[33][34][35] McCulley identified the birth of the shadow banking system with the development of money market funds in the 1970s – money market accounts function largely as bank deposits, but money market funds are not regulated as banks.[36]

The concept of hidden high priority debt dates back at least 400 years to Twyne's case and the Statute of Bankrupts(1542) in the UK, and to Clow v. Woods[37] in the U.S. These legal cases led to the development of modern fraudulent transfer law.

The concept of credit growth by unregulated institutions, though not the term "shadow banking system", dates at least to 1935, when Friedrich Hayekstated:

The full extent of the shadow banking system was not widely recognised until work was published in 2010 by Manmohan Singh and James Aitken of the International Monetary Fund, showing that when the role of rehypothecation was considered, in the U.S. the SBS had grown to over $10 trillion, about twice as much as previous estimates.[39][40]

Examples

During 1998, the highly leveraged and unregulated hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management failed and was bailed out by several major banks at the request of the government, which was concerned about possible damage to the broader financial system.[41]

Structured investment vehicles (SIVs) first came to public attention at the time of the Enron scandal. Since then, their use has become widespread in the financial world. In the years leading up to the crisis, the top four U.S. depository banks moved an estimated $5.2 trillion in assets and liabilities off their balance sheets into special purpose vehicles (SPEs) or similar entities. This enabled them to bypass regulatory requirements for minimum capital adequacy ratios, thereby increasing leverage and profits during the boom but increasing losses during the crisis. New accounting guidance was planned to require them to put some of these assets back onto their books during 2009, with the effect of reducing their capital ratios. One news agency estimated the amount of assets to be transferred at between $500 billion and $1 trillion. This transfer was considered as part of the stress tests performed by the government during 2009.[42]

Credit derivatives facilitate extension of credit

The shadow banking system also conducts an enormous amount of trading activity in the OTC derivatives market, which grew rapidly in the decade up to the 2008 financial crisis, reaching over US$650 trillion in notional contracts traded.[43] This rapid growth mainly arose from credit derivatives. In particular these included:

- interest rate obligations derived from bundles of mortgage securities

- collateralised debt obligations (CDO)

- credit default swaps (CDS), a form of insurance against the default risk inherent in the assets underlying a CDO; and

- a variety of customized innovations on the CDO model, collectively known as synthetic CDOs

The market in CDS, for example, was insignificant in 2004 but rose to over $60 trillion in a few years.[43] Because credit default swaps were not regulated as insurance contracts, companies selling them were not required to maintain sufficient capital reserves to pay potential claims. Demands for settlement of hundreds of billions of dollars of credit default swaps contracts issued by AIG, the largest insurance company in the world, led to its financial collapse. Despite the prevalence and volume of this activity, it attracted little outside attention before 2007, and much of it was off the balance sheets of the contracting parties' affiliated banks. The uncertainty this created among counterparties contributed to the deterioration of credit conditions.

Since then the shadow banking system has been blamed[26] for aggravating the subprime mortgage crisis and helping to transform it into a global credit crunch.[44]

Contribution to the 2007–2012 financial crisis

The shadow banking system has been implicated as significantly contributing to the global financial crisis of 2007–2012.[45][46] In a June 2008 speech, U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, then President and CEO of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, placed significant blame for the freezing of credit markets on a "run" on the entities in the shadow banking system by their counterparties. The rapid increase of the dependency of bank and non-bank financial institutions on the use of these off-balance sheet entities to fund investment strategies had made them critical to the credit markets underpinning the financial system as a whole, despite their existence in the shadows, outside of the regulatory controls governing commercial banking activity. Furthermore, these entities were vulnerable because they borrowed short-term in liquid markets to purchase long-term, illiquid and risky assets. This meant that disruptions in credit markets would make them subject to rapid deleveraging, selling their long-term assets at depressed prices.[27]

Economist Paul Krugman described the run on the shadow banking system as the "core of what happened" to cause the crisis. "As the shadow banking system expanded to rival or even surpass conventional banking in importance, politicians and government officials should have realized that they were re-creating the kind of financial vulnerability that made the Great Depression possible—and they should have responded by extending regulations and the financial safety net to cover these new institutions. Influential figures should have proclaimed a simple rule: anything that does what a bank does, anything that has to be rescued in crises the way banks are, should be regulated like a bank." He referred to this lack of controls as "malign neglect."[47][48]

No comments:

Post a Comment